“When translating, I feel like I'm grasping for air sometimes”

A conversation with a Japanese-English translator Yuki Tejima

I first got to know Yuki Tejima through Book Nerd Tokyo, a social media account dedicated to her literary project. Book Nerd Tokyo weaves together multicolored snapshots of books and intriguing peeks into bookstores, each accompanied by a bilingual text in English and Japanese. I was greatly receptive to Yuki’s sensibility, especially since my discovery of her project coincided with a time when I was thinking about Japan a lot.

Yuki is a Japanese-English translator and writer whose professional story is as multicolored as her literary project. After graduating from college in Southern California, she taught at a performing arts school in Okinawa and later moved to New York to work in film and television. In 2014, she moved to Tokyo. She is currently working on translation projects for authors like Risa Wataya, Mizuki Tsujimura, Kumi Kimura, and Emi Yagi. I invited Yuki to talk about all things literary but also discuss her double identity, the city of Tokyo, and how the diverse aspects of her experience help her in literary translation.

Monika: You have a fascinating background—born in Tokyo, raised in Los Angeles, and having lived in various other cities, you've experienced both American and Japanese cultures deeply. Given that they are often seen as quite different (if not polar opposites), I wonder how you perceive your identity. Do you see it as a hybrid of the two, or do you find yourself leaning more toward certain aspects of one culture over the other?

Yuki: This has definitely evolved over time. My parents are from Japan. They both went to college here, got their first jobs here, and moved to the United States in their early thirties. I think that's why they still consider themselves very much connected to Japan. I’m the opposite in that I feel like a visitor in Japan even after ten years, and I still consider Los Angeles to know me best. However, being in Japan has helped me find my voice by filling in some of the emotional holes in my identity that I remember grappling with as a teenager in LA. Those ‘where do I fit in?’ questions.

Growing up in LA, I was always shy and quiet. And that wasn’t because I was Japanese—a lot of people think that Japanese people are shy, polite, and quiet, but even in a group of Japanese people, I'm the quiet one. Contrary to what some might think, there are loud, riotous, hilarious Japanese people. Life-of-the-party types. I’m not one of them.

Growing up, I had a love-hate relationship with Japan because I had to go to a Japanese school in LA when all my friends were at the mall or the movies. Japan felt like such a disruptive presence in my life. Am I Japanese? Am I American? Am I Japanese-American? Am I American and Japanese? I've finally stopped asking those questions. As I've grown older, I've become more comfortable in my skin, and I rely less on, ‘This is an American thing in me’ or ‘This is a Japanese thing in me.’ It’s rather, ‘This is who I have come to be’. But it’s been a long road toward this.

Monika: I recall watching a YouTube show on a channel about Japan. One episode focused on Japanese people who were raised in other countries, as well as those whose parents are from abroad yet chose to raise their children in Japan. They shared a common sense of not being fully accepted by society due to this other aspect of their identity. Have you ever experienced a similar feeling of otherness?

Yuki: Absolutely. When I'm in Japan, because I look Japanese, I don't get the immediate othering, which I know that other people do. Japanese people tend to want to know your background before they can be comfortable around you. It’s just a part of the mentality.

But even if I look Japanese, when people talk to me—even for five minutes—they can tell something’s different. They look surprised and say, ‘You're not from here, are you?’ I'm proud to be from Los Angeles. I love LA, and if they’re really interested in hearing about it, which a lot of people are, I’m happy to go into detail. But if there’s no actual interest, I brush it off in most cases. It's not personal. It's not about me.

Monika: I think it takes a lot of wisdom and experience to arrive at this point where you feel comfortable with who you are. I can imagine that must have been a long undertaking, just as you described.

I wanted to talk about Tokyo a little bit. As someone with a deep appreciation for cities, I was captivated by Tokyo’s sheer size and singular atmosphere. There's something about Tokyo that feels like a universe unto itself. Do you remember your first impressions of it?

Yuki: I was born in Tokyo but moved to LA when I was four. I remember coming back to Tokyo as an adult with my parents, and my mom and I went to my former nursery school. She told me stories about walking down this cherry blossom-lined street, and the schoolyard seemed so tiny. It’s interesting to see the city through the eyes of my parents, through their deeply rooted memories.

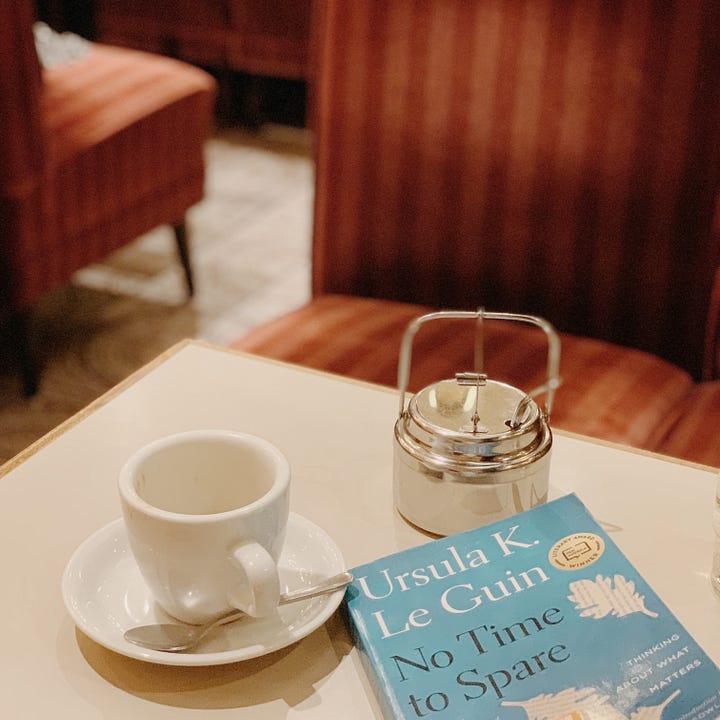

For me, Tokyo is first and foremost about the bookstores, the cafés, and the very old-school kissaten. Not the new trendy cafés from overseas—which there are many—but the small, old retro-classic cafés. I don't think that I would have become a literary translator if not for Tokyo. I've always loved reading books, and I've read books in Japanese and English all my life. When I am feeling down or not confident about my abilities, I go to the nearest bookstore or library and browse the shelves. I remind myself of what I love, and that grounds me. My temporary anxiety attack about the project I’m working on goes away as I get a great cup of coffee, a book, or a notebook. I sit down and write or read.

So, for me, Tokyo is invigorating and stimulating, but at the same time, it has a very calming effect. It helps me when I'm too much in my head—I can walk through the streets of Tokyo listening to music, looking at people's laundry hanging on their balconies, looking at kids on their bikes going to school or coming home…

Monika: I know that you’re juggling various types of work, both commercial and literary. Do you feel tension between the two?

Yuki: Right now, I’ve finished translating or am translating a few books. Hopefully, next year, I will finally have something to show people—it’s been years of work behind the scenes.

I’m working on a beloved novel titled Tsunagu in Japanese, which is called Lost Souls Meet Under A Full Moon in English, and its sequel. The first book is coming out early next year. The author is Mizuki Tsujimura, an unbelievably prolific and gifted writer that readers might know from Lonely Castle in the Mirror. She’s written so many brilliant books in Japanese that it’s impossible to choose a favorite, but the Tsunagu series is absolutely at the top of my list. I feel blessed to be translating these works.

I also have commercial translation clients with whom I've worked for many years. In commercial translation, I've translated everything under the sun—from real estate pamphlets to shampoo bottle stickers. I've done television, I've worked in fashion, in food, I know the Samurai terminology… Throughout my career, there have been many moments when I found myself thinking, why am I doing this? Will these dots ever connect? And they have. All this seemingly random knowledge helps in literary translation because I never know what type of story I will be working with.

As immersed as I am in the world of literature, I still need real-life experience to translate literature and novels realistically. Just yesterday, my husband and I were driving through downtown Tokyo, Shitamachi, where the old factories and print companies are still in operation. They are very small companies that have continued for generations. I love to drive or walk around and get a feel for the city because a lot of the novels I read and translate are set in that specific part of Tokyo.

So, in answer to your question, literary translation is very solitary work; at least the translation part is. It’s just me and the book and author, until we reach the editing stages. In commercial translation, I work with teams of people. So I have both internal work that I do on my own and this external, outward-facing work where I go to meetings and meet with people. And that helps to balance things out.

Monika: Your thoughts strike a chord with my writing experience as well. There were times when I asked myself, ‘Why am I doing this?’—especially when I was unhappy with the working situation I was in. But many of those confusing moments proved valuable in writing, understanding and processing emotions, and giving me things to ponder on and perhaps write about.

Yuki: I have a literary translation mentor who taught at a university in Japan for 30 years. She always encouraged students to go out, fall in love, and have their hearts broken because that would make them feel more, understand more, look for better words for translation. It's the living that helps in the translation.

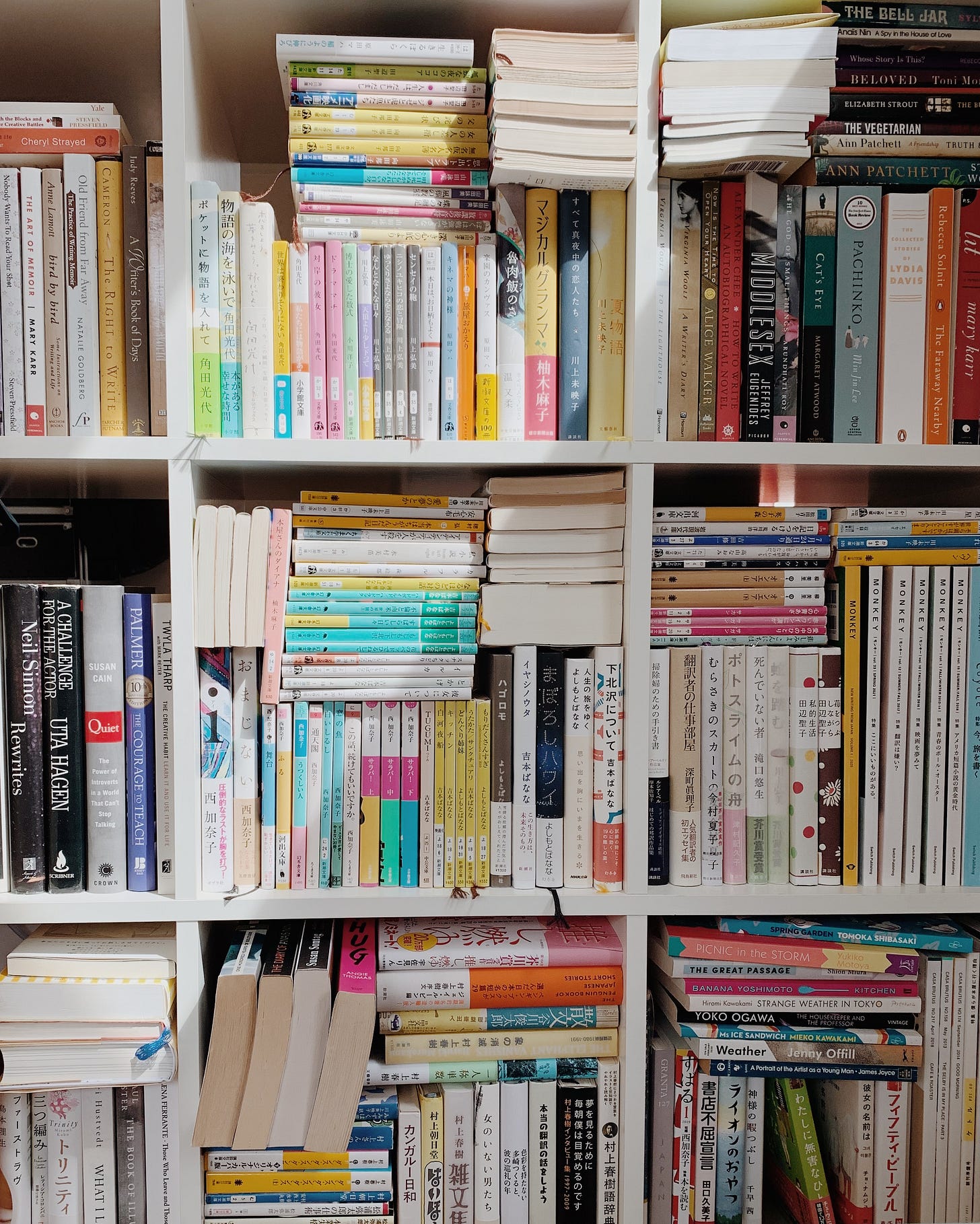

Monika: I read one of your older interviews and was delighted by the fact that you create special shelves for each project you’re working on. For example, if you’re translating a novel about female friendships, you create a shelf of novels that feature strong female protagonists and friendships of all types. Do you have such a special shelf right now?

Yuki: Right now, I'm working on a few projects, so I couldn't create shelves for each project—having too many titles in front of me is intimidating. But I have an inspiration shelf next to me. It has books that I know will support me when I feel scared or lost. The books come and go; I'm replacing them all the time. If I have my heart broken about a certain project, I need to remove all those books so I’m not reminded about it (laughs).

Monika: Four years ago, you wrote in a blog post, “I gaze admiringly at readers who have a clear idea of their reading tastes. I am not one of those people.” Has this sentiment changed at all during the past four years?

Yuki: I still read everything that I can get my hands on, but being a literary translator has made me a closer reader. I read fewer books now, whereas before, I would just tear through them. I find myself—even if I'm not consciously trying—thinking about the structure and translation in my head. So, it has become less of a carefree hobby. Obviously, I analyze every word in the books I'm working on. But I also find myself doing that with the books I read for inspiration for a certain project. When I started working on Tsunagu, I read as many books as I could by the author, who has dozens of titles. I watched her interviews on TV, watched the movies adapted from her work, and tried to put myself in her world.

I’m also discovering new authors. I didn't grow up in Japan and have never studied Japanese literature, so I didn't know where to start. I started where I felt most comfortable—usually novels written by women about female protagonists. I feel that a lot of my understanding of the Japanese mind is through these books because you get to listen to internal dialogue. You don't get that just by walking down the street.

That's how I started reading Japanese literature—it wasn't about reading the canon, the important books that everyone's supposed to be reading. I just wanted to understand what Japanese people think, specifically Japanese women.

Monika: You started the Book Nerd Tokyo website and social media account when you moved to Tokyo from the US, and since then, you have written extensively about books, bookstores, literary events, and much more. When I began my book-focused newsletter je lis trop nearly four years ago, the project became an integral part of my life. Rather than just a hobby or a pastime, it became a filter through which I saw life and myself. Has Book Nerd Tokyo had a similar impact on you? Do you feel that it has changed you in any way?

Yuki: Absolutely. Because I’d always read Japanese books and English books but not so many Japanese novels in English, I didn't know there were so many devoted readers of Japanese-translated literature, and meeting those people has been life-altering. Hearing them talk about the books that they love inspired me to learn more about Japanese literature, both translated and not. It opened up a world I didn't know I could be a part of.

Early in the project, I felt like I wanted to report back to these readers, sharing new books or authors I’m encountering in Japan. I find myself happily digging into something and trying to present it in a way that is accessible and entertaining, or at least interesting. It's been life-altering because I’m not a social person—if I’m at a party, which someone must have dragged me to, I'm in the corner talking to one person the entire night. But Book Nerd Tokyo brought out another part of me. I can talk about my own experiences through the lens of a book. I might not talk about my broken heart, but if I'm talking about a book with a broken-hearted protagonist, it might remind me of an experience I had in my life, and I might find myself talking about that.

Monika: The way you described being not social in general but very social when it comes to books resonates with me. I, too, find myself more open to others when we discuss shared experiences through a work of art rather than through straightforward questions.

I wanted to talk a little bit more about Japanese literature. During the past few years, I’ve noticed a growing interest in Japanese literature worldwide. I’m thrilled to see more authors being translated into my native language, Lithuanian. So, I’m curious if you feel the same—that there’s a growing interest in Japanese literature worldwide—and do you notice any particular trends or criteria influencing which Japanese authors are translated into English?

Yuki: There’s definitely a trend of cozy books (smiles). Japan has a lot of cozy books that you want to curl up with. I do that myself when I'm tired—curl up with a comforting book that will help unknot my brain. I do sometimes wonder if it's hard for readers to tell between the different types of books. Some of the feel-good books are considered masterpieces in Japan, and some of them are unfamiliar to many Japanese people. It's quite interesting.

I do agree with you that there is a wave of Japanese novels being translated, which is great. Just like you have books that you gravitate to in your own language, having more books in translation means you can say, ‘I like this author,’ or, ‘I don't like this author,’ or ‘I like this book by this author, but not this other one.’ Readers can have more nuanced conversations.

Monika: Do you also track which authors are being discovered and gaining attention in Japan? Who gets to be translated into Japanese?

Yuki: That's a good question because there is such a long history of reading translated literature in Japan. When I walk through a Japanese bookstore and look at the shelves, I’m often stunned: ‘Oh, my God, that's translated already? This just came out in the US!’

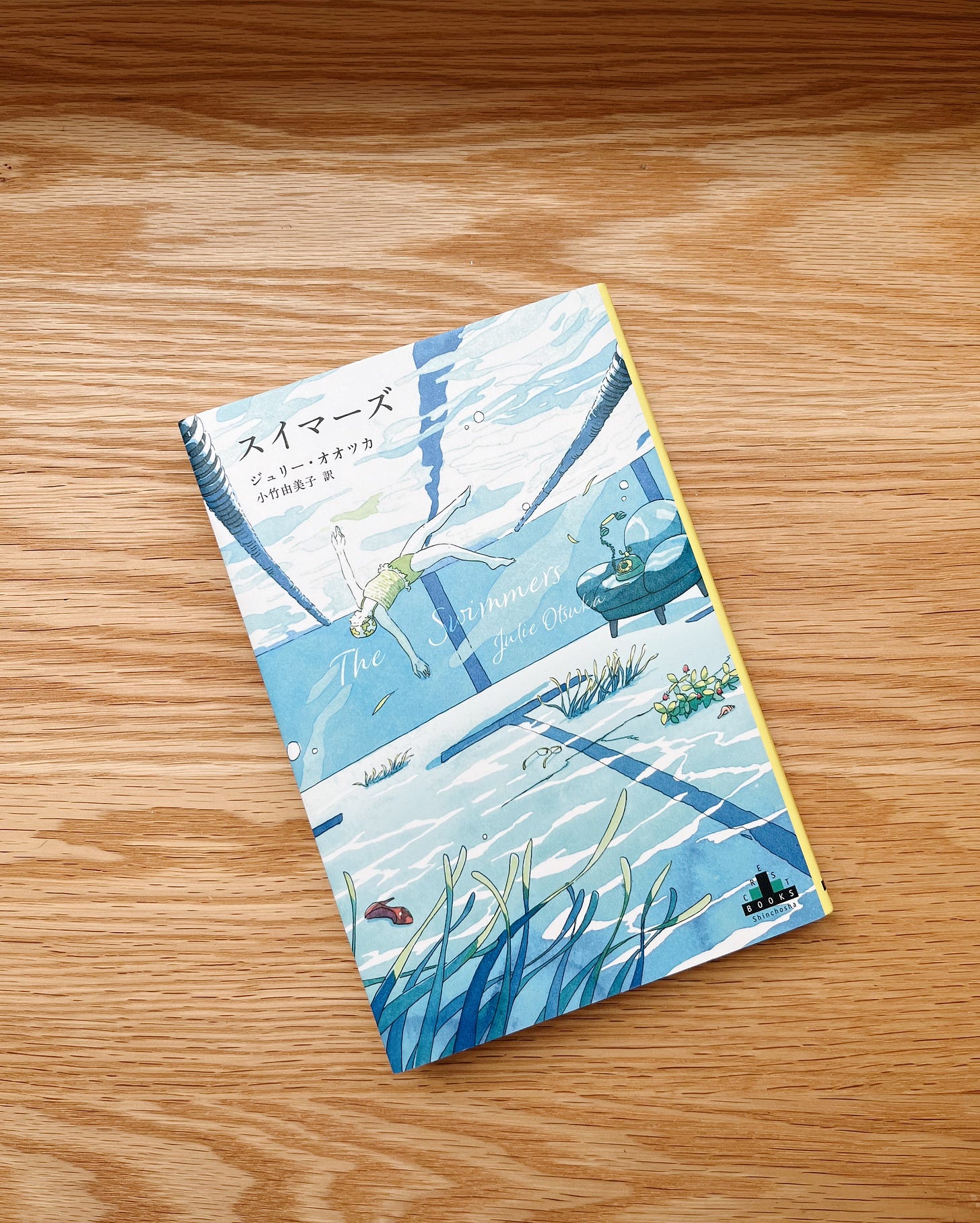

This is The Swimmers by Julie Otsuka (shows a book). I remember reading it last year in English, and it's out now in Japanese, in Yumiko Kotake’s translation. I wholeheartedly recommend it, both in English and Japanese. I'm always amazed by the quality and range, like you said, of Japanese literature from abroad, not just from English. Korean to Japanese translations are coming at a phenomenal pace right now.

Japanese people realize that if it weren't for these translators, they would not be able to read the books that the rest of the world reads. And so they deeply respect their translators. If you look at this cover, you see the title The Swimmers is in Japanese, and here is the author’s name, along with the translator’s name in the same size font. It's a given that translators are credited for the work.

Monika: I know it's a philosophical question, but I still wanted to ask: what do you consider a good translation? How do you recognize it when reading?

Yuki: Accuracy is essential, of course, but not necessarily on a word-for-word or line-for-line level. It’s more about capturing a feeling. There’s definitely a feeling to Julie Otsuka’s work, for example. Her books are about rhythm, tone, voice, and the feeling those elements create. If that feeling is captured in Japanese, I don't care so much about word or sentence order. Japanese and English grammatically are almost entirely opposite—you have to flip the order of every sentence, so there's no way to translate it word for word anyway. But if I'm moved by a book in English, and I get the same feeling when I read the book in Japanese, I know the translator has captured it. And I am in awe.

When translating, I feel like I'm grasping for air sometimes. I'm obviously trying to be as accurate as possible. But if it's too literal, or if it feels too difficult to read in English, then it reads like a translation. The reader can feel it. If that happens, I try to go back to the Japanese version and feel what I felt on that page, and try to recreate that in English, even if that means moving a sentence around.

Monika: How do these three roles—translator, writer, and reader—interact with each other? Do they nourish each other? Do they compete with each other?

Yuki: This year, I've been reading and translating but haven’t been writing my own words. Last month, I had to write something from scratch for work, and I drew a blank. The writing muscle has been asleep for ten or eleven months while I've been living in other people's words and minds.

I told myself, ‘You can do this. You have thoughts, too!’ But my mind kept saying, ‘Give me some lines to translate.’ I had to take myself to a bustling café, where I could hear people's conversations and interact with their words. That helped trigger something.

For me, reading is always happening. The conflict is more between writing and translating. When I'm too immersed in one thing, it's hard to switch over and do the other thing. I’m hoping to start writing my blog again so it keeps the muscle from completely failing me when I need it.

Monika: I was curious to hear your thoughts on this because I am interested in the dependencies between creative processes and how they influence one another. After three years of writing about authors and books, I began thinking more about my own words. One day, I realized I had created a fully formed story and didn’t want to put books in it. This led me to fiction writing, a shift that has been both intriguing and disorienting. Although I still enjoy writing about books, I don’t do it as much as I used to. Transitioning from one creative space to another after so long has been both unsettling and eye-opening.

Yuki: How did you get through that? Did you keep writing?

Monika: I took a break from writing about books for a few months, but I never stopped reading. I know some writers don't read while working on their own stories because they don't want outside influences, but I like to be reading all the time. Sometimes, a story that shows me what I don't want to write about; sometimes, a story that points me in a direction I had already intuited but needed another push to explore. So, I stuck to this new priority of fiction writing and put everything else on pause.

Yuki, what is the number one thing you’re most looking forward to in the upcoming months?

Yuki: Sleeping. I’m sorry, that’s so boring, but the stifling heat in Japan seems to have finally noticed that it was overstaying its welcome, and in its absence, life is suddenly better. I look forward to being able to sleep again. Also, your newsletter and this interview have helped to awaken a part of me that hasn’t been tapped in months, and once I complete the projects I’m working on now, I hope to read and write freely and unravel my mind, which feels so tightly wound now. And, of course, I’m excited and grateful to share some of the titles that will be published in the coming months. Thank you again for letting me talk about so much, Monika!